Interview with Julianne Nash

Tiny Birch Residency Director Elena Kendall-Aranda talks to the artist about her artistic process.

Julianne Nash is a New York City based artist who’s current work utilizes algorithmic digital collage techniques to create densely layered landscapes that seek to understand our ineffable climate crisis on a micro scale.

TINY BIRCH:You’ve worked extensively with the natural world under an environmental point of view. How did these concerns become so central to your work?

Julianne Nash: At a young age, the natural world became a source of inspiration for me long before I was conscious of my growing relationship to it. Moving to New York City, however, threw my beliefs of environmental protection into sharp relief, as I was surrounded by a world that I came to realize I was acutely fearful of.

The immeasurable amounts of trash, consumerism and only small patches of greenery really instilled a call to action in me — I saw the city as a place that was the polar opposite of how I related to the world. It didn’t take me long to realize that I needed to lean into my fears of environmental collapse and use my medium as my voice. Most photographs about climate change have a doomsday approach to reportage. Although I do think that it is absolutely necessary to disseminate images of, for example, our ice caps melting and our rainforests on fire, I realized most people, myself included, were seeing those images as something separate to their reality — as if the world is collapsing in another universe while we all continue to go about our days. Since then, I have been interested in making images that hint to various themes of environmental collapse that are less literal than the media presents. I want people to look at my images and think about how familiar the scene looks in hopes that they can re-stage their preconceptions of climate change into a more localized and subtle view.

TB:There have been study findings that indicate human–technology–nature interconnectedness is a possible conduit for establishing a role for digital technology beyond social networking, computing, information gathering and gaming to engage with nature. There is an argument for digital eco-artists being at the vanguard of creating a new sense of aesthetic and environmental engagement, proportions of which emerge as transformative possibilities. The art experience of digital eco-art could change from being a contemplative one to a living experience. Where do you situate yourself in this intersection of eco-art and digital art movements?

JN: We are oversaturated with images everyday — all day. Because of this, I am interested in using the fallibility of digital tools to parallel our inevitable environmental destruction. I closely align with many of the ideals of the Impressionist movement; believing that the accumulation of information can hint as something greater than reality. Trough my adaptive forms of digital collage, I can create photographs that have unfathomable amounts of detail. I love to make massive prints that force viewers to confront the minute details of the landscape that would otherwise be missed.

There is a quote from the book The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace Wells that is always reverberating in the back of my mind: “On-screen climate devastation is everywhere you look, and yet nowhere in focus, as though we are displacing our anxieties about global warming by restaging them in theaters of our own design and control—perhaps out of the hope that the end of days remains ‘fantasy’.”

Because of my use of digital collage, I have come to understand that I am a keen participant in the act of controlling the restaging of this devastation. My images are of nowhere, yet everywhere — I collage together reality into a more overt metaphor for what I am experiencing. Although this has been an ever-present dichotomy in my work, being half participant in the status-quo and half critic, as an eco-artist I am distinctly aligned with the theories of digital art. I often think about how Ansel Adams’ photographs paved the way for the environmental movement that we know and love today; he used the medium of his time to create something that the world would knowingly appreciate — and thus helped to create protective policy. I think that contemporary artists simply need to use the tools are their disposal to work synonymously to those that came before.

My intention is to have the first and last images of the series become similar to a feedback loop — once you reach a certain point, you will start at the beginning again. The seventh extinction, if you will.

TB: I can see that the theme of life and death/the cycle of life inspires you a lot. Can you tell us why it is important for you?

JN: The life cycle is a continual theme that seems to always re-appear in my process. I first began to look at the landscape with a sense of memento-mori shortly after a dear friend of mind passed away far too young.

I started to look at the landscape of my hometown as a place of heartbreak: his loss and my personal childhood struggles became somewhat intertwined in my early years of undergrad. These metaphors re-appeared after losing both of my grandparents during my graduate studies. They both meant more to me than words could ever begin to express, as they were more parental figures to me than grandparents. Because I needed to focus on my degree at the time, I felt like I didn’t have a chance to mourn their loss; so I channeled all of that pain into making photographs of floral bouquets as they died, one for each of them. The resulting images became more about the nebulous zone between life and death rather than the heartbreak itself, which became a driving theme throughout all of the work I have created since.

Although I certainly project my own experiences on the way I look at the environment, this liminal space between life and death is clearly evident within the climate as well. Specifically, for my work “Ennuipocalypse” I want the images to feel cyclical in the sense that the viewer is unaware of where they exist within the timeline of extinction. My intention is to have the first and last images of the series become similar to a feedback loop — once you reach a certain point, you will start at the beginning again. The seventh extinction, if you will.

TB: Though your work deals with some dark topics, a lot of your pieces are strikingly beautiful. How do you respond to people who might say your work being so pretty lends to gender stereotypes in the art world, which equate beautiful and pretty to feminine and superficial? What role does beauty play into your process?

JN: The feminist in me absolutely hates the notion that, because I am a woman, and I am making beautiful photographs, that there is something inherently superficial to my work in many critics eyes. I have seen numerous of my male counterparts making strikingly beautiful — and colorfully seductive— work only to be raved about for their feminine connotations within. Although I railed against that idea while in grad school, I somewhat understand the superficiality of beauty within my work. I ascribe to the notion that beauty is merely an entrance point into my concepts, a tool used solely to grab the viewers attention and lure them into the actual themes I am interested in.

However, my relationship to this question has shifted throughout various projects. For example, the colors in “Agglomeration” or “The Exiles” are substantially more alluring and seductive than the subtle color tones in “Ennuipocalypse” which I think has a lot more to do with my perception of the world than anything else. Although I have high hopes for climate policy to change our current trajectory, I tend to be a skeptic that there is ever a chance that we could possibly stop the corporations with the largest emissions (read: listen to “Drilled: A True Crime Podcast About Climate Change” if you disagree!). They are still beautiful, but certainly not as overtly “feminine”. For the other two projects, I’m contenting with my own loss’ and traumas so I tend to colorize those more; maybe because I am more hopeful of change — or maybe it just makes it easier to hide behind the seductive beauty a little.

TB: What was the impetus for putting those abstract ideas into visual form? Why did you feel that was so important for you to be doing?

JN: I have always struggled to articulate myself in non-visual forms. I am often baffled when speaking to people from my childhood who were entirely unaware that I have been struggling with anxiety and depression since I was a pre-teen. The only way I have ever been able to articulate the mess inside my mind is through my art practice, as cliche as that may sound. I’ve been using art therapy for my entire life — and many themes from my early high school paintings have actually been reappearing in my current work, which I find fascinating. On a personal level, it is unfathomably helpful to excavate these abstract ideas and put them on paper; and on a larger level I think that contending painful realities visually can hopefully help someone else understand something inside them; or…if I’m lucky, make them a climate activist!

TB: How has your time a Tiny Birch helped you in your practice?

JN: I desperately needed to detach from reality after the absolute mess that has been the past year. Apart from not being able to travel to make images for the past year, being stuck inside my tiny Brooklyn apartment with my fiancé left me feeling fundamentally stuck as an artist: physically, mentally, and emotionally. Coming here not only allowed me to breathe a little, I have also been able to gather thousands of images to use in collages over the next few weeks. I have so many images planned — and I am very excited about one that I just finished of erosion alongside Lake Champlain. It’s been wonderful to watch spring come alive while here (and winter return!). It’s given me a new sense of excitement for what’s to come.

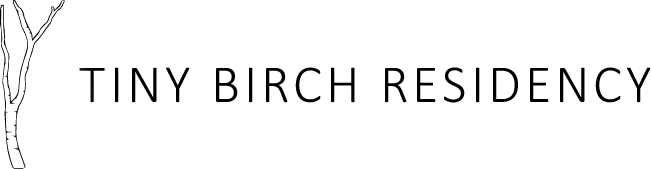

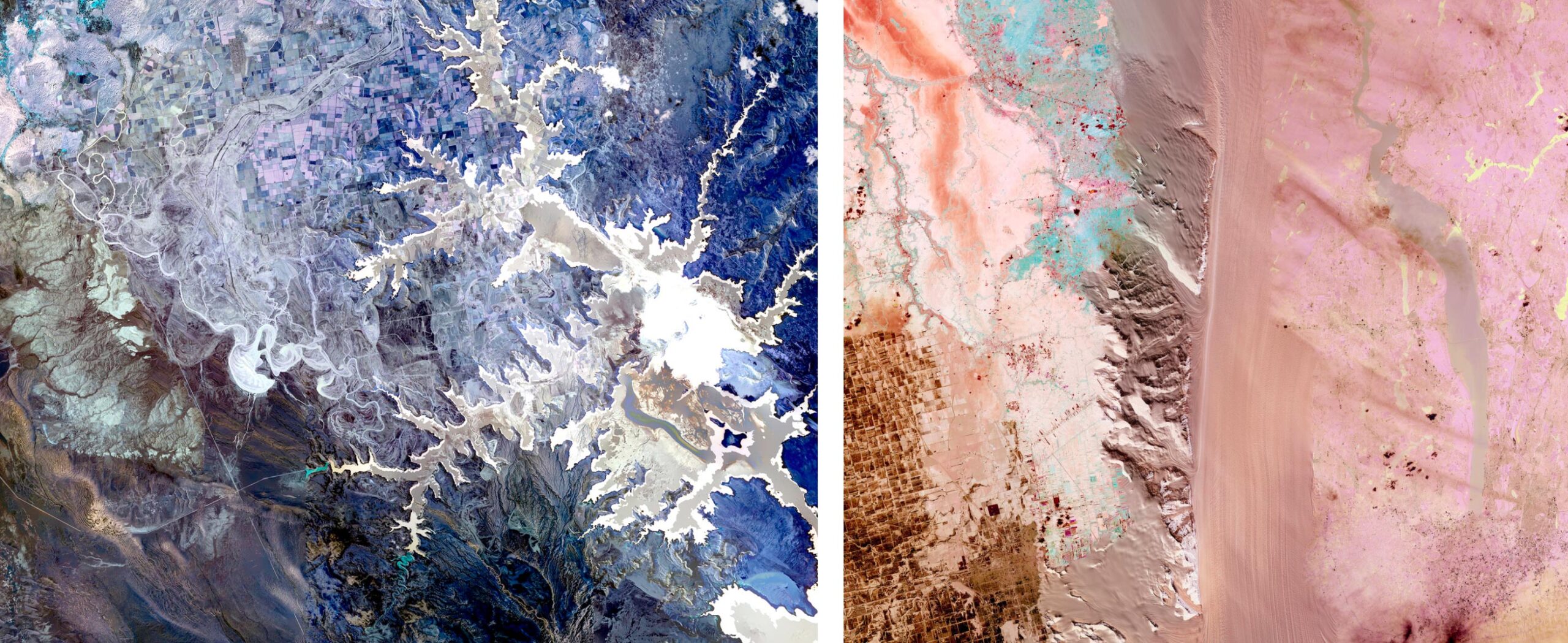

Image captions by order of appearance:

- From the series “A Preternatural Paradigm”

- Nash at her studio. © Dana Stirling

- Grandpa’s Flowers Post-Mortem (Focus Stack, 74 Images, Re-stacked 5 Times Upon Itself)

- Grandma’s Funeral Flowers (Focus Stack, 65 Images)

- NASA Stack No. 7 (Colorado River Delta, Lake Powell and Alluvial Fan)

- NASA Stack No. 9 (Flooding in North Dakota and Thailand, Byrd Glacier Antartica, Phosphate Mines Jordan)